The Art and Science of City Carbon Budgets

In 2017, the City of Oslo pioneered a game-changing approach to fighting climate change: the carbon budget. The budget sets a cap on how much the city can emit before 2030, when Oslo plans to become carbon neutral, and divides that amount into annual budgets. The City’s finance department considers the budget alongside its finances when making decisions. The City describes it as the “most important management tool” for achieving its ambitious goal of net-zero emissions by 2030. We couldn’t agree more.

Why is it so critical? Different levels of government around the world have adopted net-zero targets for points in time in the future, but, on their own, these are insufficient tools to meet the Paris Agreement’s target of limiting global warming to below two degrees Celsius. The trajectory of the emissions reduction path matters, too. Climate change is a function of how much greenhouse gas we emit into the atmosphere in total, not just when we emit it. If emissions rise too much before we hit carbon neutrality, we will not prevent catastrophic global warming.

In addition, there is a temporal disconnect. Cities typically make budgetary decisions on programs and investments on short timelines, making it difficult to align these decisions with 10- to 30-year emission reduction targets.

We believe that carbon budgets are a powerful tool for cities to tackle these challenges. In addition, they offer a number of advantages over the conventional target-setting approach:

- The idea of a budget is simple, and it is a familiar approach to planning in local governments. Similar to the financial budget, a carbon budget includes revenues (annual emission limit), expenses (emissions), and deficits/surpluses (annual emission limit minus emissions).

- A carbon budget provides an overarching framework for GHG emissions management, extending over multiple years and over all aspects of community social and economic activity.

- Carbon budgets align with the science of climate change by recognizing cumulative emissions will determine the extent of global warming.

- The carbon budget aligns with decision-making frameworks used by local governments for capital and operating budgets—frameworks in which investments, costs, and benefits are assessed over multiple years and often involve trade-offs between early action and deferred spending.

- Like a financial budget, the carbon budget provides a framework for achieving the organization’s objectives; responsibility for some pieces of the budget can be allocated to different departments, allowing them to manage their share of the budget and identify priorities for early action that fit best with their mission and objectives.

- When combined with effective monitoring of emissions, the carbon budget also provides a framework for reporting progress on a consistent basis from year-to-year, while ensuring transparency and the feedback needed to make periodic adjustments to the budget.

Calculating a City’s Carbon Budget

The carbon budget forms a direct connection between the science of climate change and the policies and spending patterns of the local government. It provides the long-term context for investment planning, as well as an accountability framework for short- and medium-term commitments to mitigate climate change.

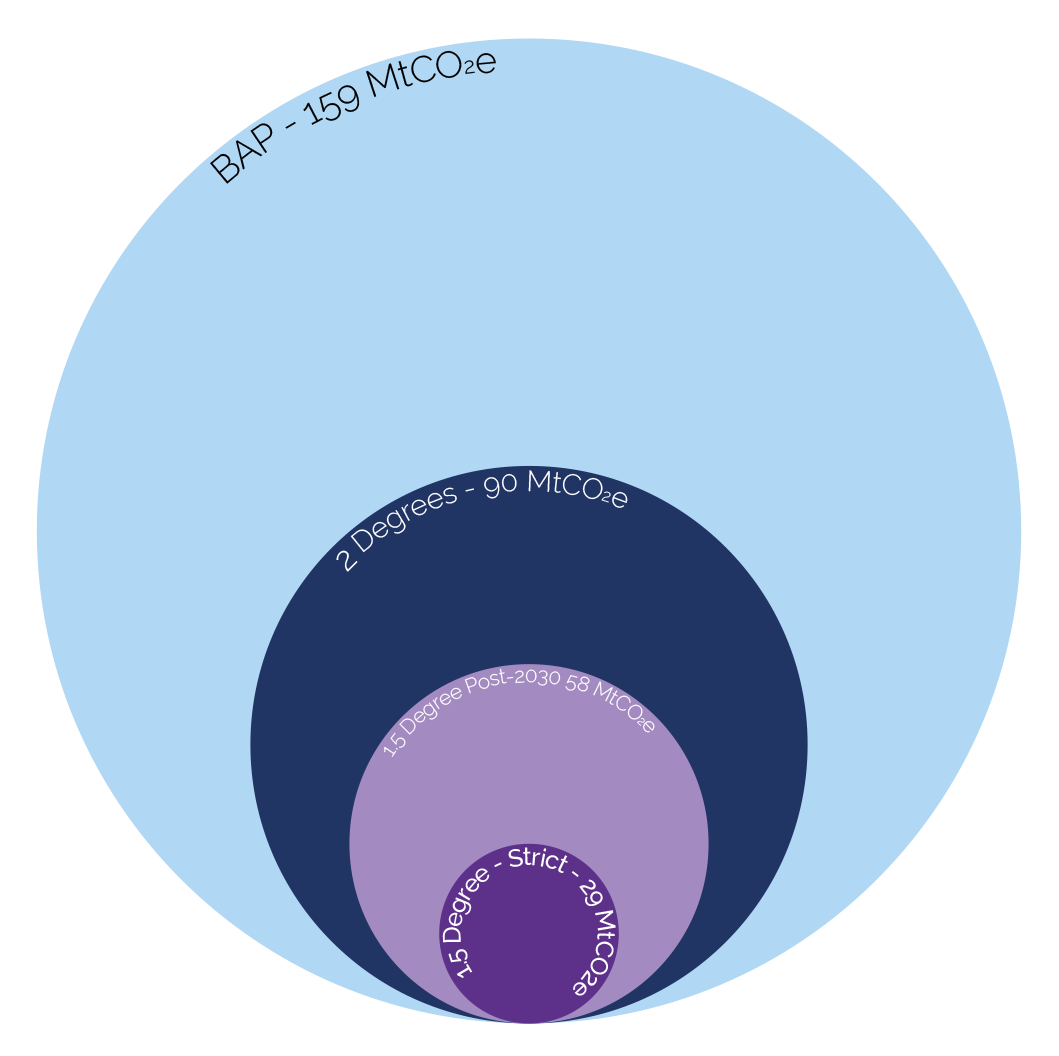

In 2017, C40 published the report Deadline 2020: How cities will get the job done. The report assessed the contribution of the C40 cities to the Paris Agreement’s aspirations of limiting climate change to within 2 degrees and, ideally, 1.5 degrees. GHG emissions reduction trajectories, as well as potential actions to achieve those trajectories, were determined for each of the C40 cities. C40 used a three-step approach to identify the carbon budgets:

- Determine the global carbon budget for safe levels of warming of below 1.5 and 2 degrees.

- Identify an approach to allocate a fair portion of this budget to the C40 cities.

- Use the contraction-and-convergence approach, in which high emitters reduce emissions to a common per capita emissions rate and low emitters increase to that rate by a set date.

We have used C40’s approach to calculate carbon budgets for Edmonton, Durham, and Whitby, but our non-C40 clients are also looking for a carbon budget approach that is suitable to their size and circumstances, leading us to develop a generalizable approach for city carbon budgets.

The SSG Carbon Budget Method and Tool

The most complex consideration is that of fairness. Science cannot tell us what is a fair share of the remaining emissions pie for any particular city—this is a question of values, historical circumstance, and, ultimately, politics. There is a generally accepted principle that rich, emissions-intensive countries must reduce their emissions faster and further than poor and developing countries, and that they must also contribute most of the investment that will be required to flatten the global emission curve. The devil is in the details of exactly how to apply such a principle.

EcoEquity and Stockholm Environment Institute have developed a web-based calculator that allocates carbon budgets to countries that are aligned with scientific guidance, while allowing users to adjust equity settings. To downscale these totals to cities, we take the baseline emissions inventory of the city as a share of the country’s emissions for that same year. We then apply this share to the annual carbon budget identified in this calculator. We chose this approach over the application of a per capita emissions share because cities have emission patterns that are different from national emission patterns.

SSG is working with Pathway to Paris to design and build a carbon budget tool based on these design principles that establishes carbon budgets for nearly 300 cities around the world. We hope the tool, which will be released later this year, will inspire more cities to adopt the carbon budget approach to effective and accountable science-based mitigation strategies.

The 1000 Cities Carbon Calculator, created by SSG and Pathway to Paris, will be released later this year.

Our calculations indicate that reducing emissions is more urgent than we anticipated. For example, applying the SSG Carbon Calculator to Vancouver shows the city will use its remaining carbon budget in three to five years, with the lower limit corresponding to a scenario in which individuals earning less than $7,500 per year would be exempt from contributing to emissions reduction targets.

Carbon budgets provide a scientific and systematic framework for mounting the emergency response that has become an imperative for communities everywhere. The pace of emission reductions required to stay “within budget” is overwhelming and the implications are clear: there is no time left to delay urgent action to slash emissions and develop negative emissions technologies.

To get in touch about how we can help your community tackle climate change, contact us here.

–

Ralph Torrie is a Senior Associate at SSG and an internationally recognized expert in the field of sustainable energy and climate change response strategies for governments and business. He pioneered many of the conventions now used throughout the world for local government GHG emissions planning, and he was the principal author of Canada’s first low-carbon scenario analysis—the first such analysis done anywhere in the world.

Yuill Herbert is a Co-Founder and Principal at SSG. He has led dozens of climate action plans, including City of Winnipeg’s Climate Action Plan, City of Toronto’s TransformTO, Town of Bridgewater’s Community Energy Investment Plan, City of Ottawa’s Energy Transition Strategy, and City of Edmonton’s Energy Transition Plan Update.